Causal Discovery with Reinforcement Learning

Published:

This is a blog post credit to Elijah Cole and Avinash Nanjundiah

Introduction

In this blog post, we discuss the recent paper Causal Discovery with Reinforcement Learning which was published at ICLR 2020. We also review relevant background knowledge and context, so this post should not require prior knowledge of causal inference or reinforcement learning.

Background

Causal Inference

Typically, the goal in supervised machine learning is to use data to estimate the conditional probability $p(y|x)$. This quantity tells us about the correlation between $x$ and $y$. But what if we intervene and force $x$ to take on a certain value? In this case we want to estimate a quantity denoted $p(y|do(x))$. This is discernible only if we know the causal relationship between $x$ and $y$: does $x$ cause $y$ or does $y$ cause $x$? For example, let $y$ be our body temperature and let $x$ be a thermometer reading. If $x$ is high, we expect $y$ to be high as well based on $p(y|x)$. However, if we wanted to skip school, we could hold the thermometer up to a lamp and heat it. Given the new $x$, we would not then estimate that we have a fever, as $p(y|x)$ might imply. This is due to the causal relationship between $x$ and $y$, where in this case $y$ causes $x$ and not the other way around. Thus, it is easy to see that $p(y|do(x))$ is different from $p(y|x)$.

In the preceding example, it is easy to figure out the causal relationships between variables by performing an intervention - we can change the thermometer reading, but body temperature stays the same. However, interventions can be difficult or unethical to perform. In such cases we only have access to observational data. In order to perform causal inference, we must know the causal relationships between variables a priori. These causal relationships are canonically represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where each node is a variable and each directed edge is a causal relationship. Given a DAG we can form a “mutilated” causal model, which is the original DAG with all incoming edges into the $do()$ variable removed. Then, using rules of do-calculus”, it is possible to approximate the distribution $p(y|do(x))$ in terms of quantities that can be estimated from observational data. But how can we find out what the DAG is, especially in more complex scenarios?

Causal Discovery

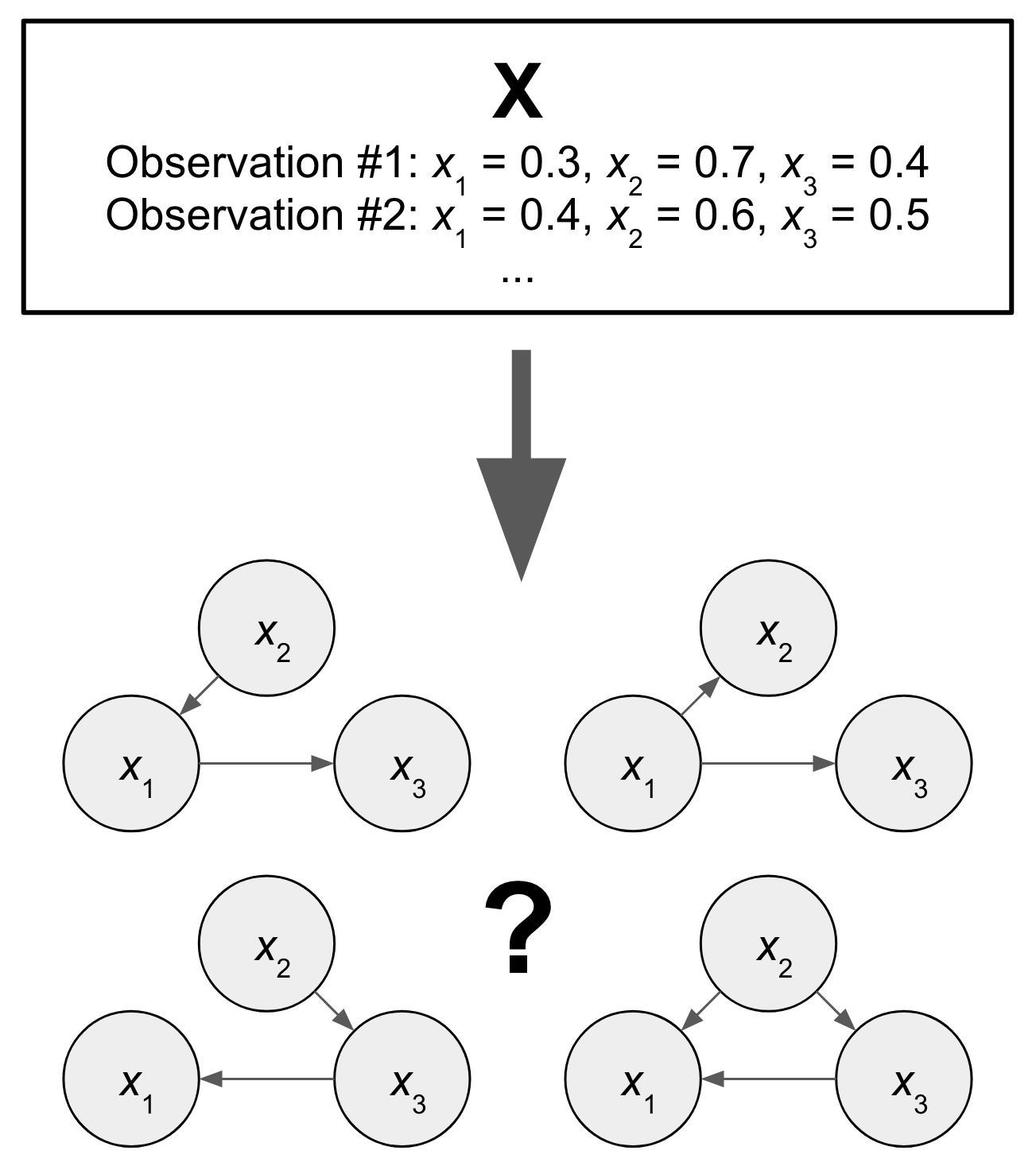

As described in the previous section, causal inference is predicated on having access to a DAG which describes the causal relationships between variables. Generally, we do not have access to interventional data such as a randomized control trial to infer causality, meaning that we must use observational data. In causal discovery, the goal is to find a DAG that is consistent with observed data.

One approach is constraint-based causal discovery. The PC algorithm is one example, which aims to find a Markov equivalence class (MEC) that is consistent with the data. This algorithm works by starting with a complete undirected graph, and iteratively removing edges through independence testing based on observed data. Edges are first removed if variables are unconditionally independent. Then they are removed if conditionally independent given another variable, a set of 2 other variables, and so on for increasing sets of conditioned variables. Orientation is inferred based on which variables led to conditional independence. This approach suffers from the multiple hypothesis problem during independence testing, and small errors in estimation can lead to large discrepancies in the inferred MEC.

Another common approach is score-based causal discovery, Score-based methods attempt to find a graph G such that:

where $S$ is a score function that is inversely proportional to how “good” $G$ is for explaining the observed data $X$. One algorithm in this class it greedy equivalence search (GES). GES starts with an empty graph, and iteratively adds directed edges to maximize a particular score at that step. A commonly used score is the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), an extension of a likelihood function that accounts for the number of parameters to prevent overfitting:

where $n$ is the number of samples in the observed data, $k$ is the number of parameters, and $\hat{L} = p(x|\hat{\theta}, M)$ is the maximized likelihood of the model $M$. The specific nature of likelihood function depends on the assumed causal relationship between variables. Acyclicity is checked at each step. While GES leads to a global maximizer given infinite data, finite datasets do not carry the same guarantee.

Another notable causal discovery method is the functional causal model. These models takes advantage of the fact that it is easier to recover effect from cause than vice-versa. The idea is to incorporate a noise term $\epsilon$ that is independent of cause but not the effect. Testing for this asymmetry can determine the directionality of an edge. This enables one to distinguish among different graphs in a MEC. An example is the linear, non-Gaussian, and acyclic model (LiNGAM).

Reinforcement Learning

In this section we will briefly review reinforcement learning and set notation for the next section. Reinforcement learning (RL) involves an agent (the learning algorithm) in a given environment. At any given moment, the environment occupies a certain state ($s$). Given the state and an agent’s action ($a$), the environment produces a certain reward ($r$). The agent must learn a policy ($\pi$), a mapping from the current state to an action believed to generate a high reward. This policy can be stochastic as well, generating a distribution $p(a|s)$ over possible actions.

One of the most important RL algorithms is the REINFORCE algorithm, which belongs to a class of methods called policy gradient methods. REINFORCE is a Monte-Carlo method, meaning it randomly samples a trajectory to estimate the expected reward. With the current policy $\pi$ with parameters $\theta$, a trajectory is “rolled out”, producing

The gradient of the expected reward $J(\theta)$ is: where where $\gamma$ is the discount factor which governs the value of immediate rewards vs. future rewards. REINFORCE stores the log policy probabilities and rewards for each step, calculates the discounted reward for each step, and then computes the gradient to update the parameters.

The issue with REINFORCE is that Monte-Carlo sampling of trajectories introduces high variance into the log probabilities and cumulative rewards, since trajectories can be very different. This leads to a noisy gradient and unstable learning. Additionally, cumulative rewards can oftentimes be 0, prohibiting learning. One way of dealing with this issue is through an actor-critic architecture. In this method we replace $G_{t}$ with a more stable function, such as the $Q$-value:

which estimates the expected cumulative reward. Since this is an expectation, it is more stable and less variable. In order to learn this $Q$ function, a neural network must be introduced, known as the critic. Another neural network, the actor, updates the policy distribution using the critic’s output. This actor-critic model with REINFORCE is the algorithm used for causal discovery in what follows.

Causal Discovery with Reinforcement Learning

How can reinforcement learning be used for causal discovery? In the standard view, the goal of reinforcement learning is to learn a policy which can be used to perform some task on unseen data. For example, reinforcement learning has been used to develop agents that can play board games like Go. Once the policy is learned, it can be used to play against human opponents. However, in this paper reinforcement learning is used as a search algorithm, where the goal is to find a “good” state. The policy learned during this search is simply discarded at the end.

Let’s talk about how this maps on to the causal discovery problem. Suppose we are interested in the causal relationships among $d$ variables $x_i$ for $i = 1\ldots, d$. Suppose we make $m$ observations of these $d$ variables, and collect these observations in $X \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times d}$. Recall that in score-based causal discovery, we want to solve

where $S$ is a score function that measures the extent to which $G$ is inconsistent with our observed data $X$. This is an NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem, primarily because the DAG constraint is difficult to work with.

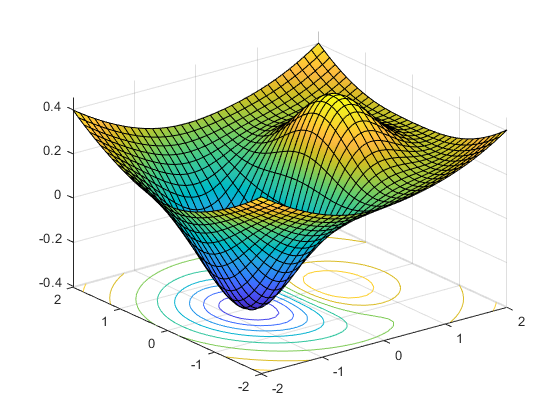

One way to attack this problem is to transform it into a continuous optimization problem and apply gradient-based methods. The key to this approach comes from a recent paper which describes a user-friendly characterization of DAGs. They constructed a smooth function $h: \mathbb{R}^{d\times d} \to \mathbb{R}$ with the property that a directed graph with adjacency matrix $A$ is acyclic if and only if $h(A) = 0$. With this tool in hand, a number of recent papers have replaced the combinatorial optimization problem with some variant of

where $S’$ could be either the score function itself or a differentiable surrogate and $A$ is the adjacency matrix of $G$. The problem with these approaches is that $S$ is often not differentiable, and it can be difficult to find a differentiable surrogate. The consequence is that only a few score functions are compatible with this continuous optimization formulation.

This is where reinforcement learning can help. The key idea is to design a reward that captures both the score function and the DAG constraint. Then we can use standard reinforcement learning techniques to select and evaluate a sequence of graphs, finally returning the graph with the highest reward. The result is a learned heuristic for score-based causal discovery that is compatible with arbitrary score functions.

So what does the reward function look like? It has three components:

- a score function $S(G)$, which penalizes inconsistencies between the graph $G$ and the observed data $X$; and

- a hard constraint term $I(G\in\mathrm{DAGs})$, which applies a fixed penalty if $G$ is not a DAG; and

- a soft constraint term $h(A)$, which applies a graph-dependent penalty if $G$ is not a DAG.

First, let’s discuss the score function. The authors choose to use an established score function, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The BIC requires access to a likelihood function for a graph $G$ given observed data $X$. To make this tractable, the authors make several assumptions. First, they assume that a DAG $G$ gives rise to observed data via

where $f^i$ is an arbitrary function and $\mathbf{x}_{\mathrm{pa}(i)}$ denotes the parent nodes of node $i$. By making further simplifying assumptions about the causal relationship function $f^i$ (e.g. linear, quadratic) and noise $n$ (e.g. Gaussian, Gaussian through a linearity), one can evaluate how well a DAG accounts for the observed data. We leave a full description of the score function to the paper, but we do want to note that the authors name two variants of the BIC score function for use in their experiments: BIC (which makes no assumptions on noise variances) and BIC2 (which assumes the noise variances are equal).

Now let’s discuss the DAG constraint terms. A reasonable question is: Why isn’t the soft constraint term sufficient on its own? It turns out that there are cyclic graphs which correspond to small values of $h$, so $\mu$ would have to be quite large to make the second term alone produce DAGs consistently. In the OpenReview discussion, the authors note that they originally tried using only the hard constraint term but found it performed poorly.

In any case, the full reward is so the goal is to solve

Is this optimization problem equivalent to our original problem, i.e. minimizing $S(G)$ over all DAGs $G$? It turns out the answer is yes, so long as

where

- S_U$ is an upper bound on $S^* = \min_{G\in\mathrm{DAGs}} S(G)$; and

- $S_L$ is a lower bound on $S$ over all directed graphs $G$; and

- $h_\mathrm{min} = \min_{G \notin \mathrm{DAGs}} h(A)$.

In the paper the authors give recommendations for meeting this condition in practice - it just comes down to estimating a couple quantities and setting $\lambda$ and $\mu$ based on those estimates. They also recommend gradually increasing $\lambda$ and $\mu$ throughout the course of training - we leave those details to the paper.

The training objective is to maximize

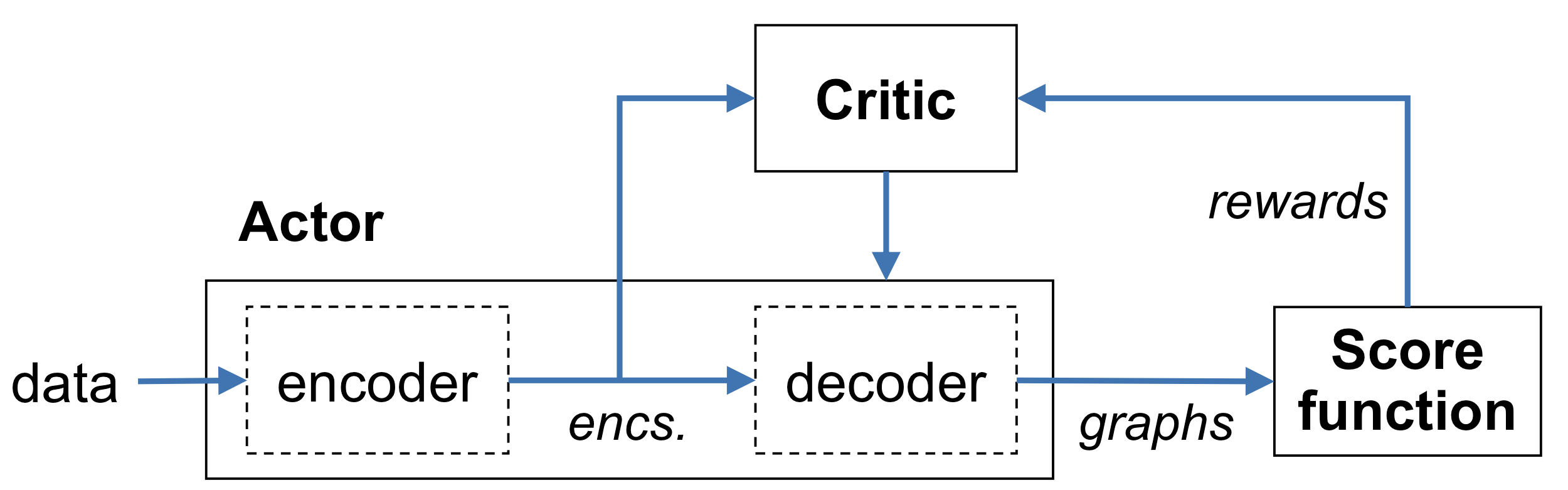

where $\pi$ denotes the policy, $\psi$ denotes the parameters for the policy / graph generator / actor (described below), and $s$ is derived from a batch of (slightly reformatted) randomly sampled observations from $X$. In particular, we randomly sample some number of rows of $X$; if we call the result $X’$ then $s$ consists of the columns of $X’$ which we denote by $\tilde{x}_i$ for $i = 1,\ldots, d$.

The actor has an encoder-decoder structure. The encoder is implemented as a Transformer, and maps each $\tilde{x}_i$ to a latent representation $enc^i$. This is the input to the critic (see below) as well as the decoder. The decoder consists of $d^2$ single-layer networks of the form

where $W^1, W^2$, and $u$ are learnable parameters. Each network $g^{ij}$ models the causal relationship between variable $i$ and variable $j$. The decoder produces a graph by generating an adjacency matrix $A$ entry-by-entry. In particular, $A^{ij}$ is sampled from the Bernoulli distribution with parameter $\sigma(g^{ij}) \times I[i \neq j]$ to determine whether variable $i$ causes variable $j$, where $\sigma$ denotes the sigmoid function. The policy / graph generator / actor gradient $\nabla_\psi (\psi | s)$ is estimated using the REINFORCE algorithm.

The critic is implemented as a 2-layer feed-forward ReLU network that takes the encoded representation of $s$ (i.e. $enc^i$ for $i = 1,\ldots,d$) and estimates the reward - it is trained using the MSE loss between the predicted and actual rewards.

To evaluate their method, the authors carried out experiments on synthetic and real datasets and evaluated how well their algorithm did at recovering the true DAG. Note that each of the synthetic datasets is one where it is known that the true DAG can be recovered from observed data.

The synthetic datasets correspond to different data generating processes:

- Linear $f_i$ with Gaussian noise.

- Linear $f_i$ with non-Gaussian noise (Gaussian noise passed through a nonlinearity).

- Quadratic $f_i$ with non-Gaussian noise (as above).

- $f_i$ sampled from a Gaussian process with Gaussian noise.

The real dataset is a protein signaling network whose causal graph is considered well known.

According to their results, the method presented in this paper performs as well or better than competing approaches in all cases. A few observations about these experiments:

- Strangely, it seems that for linear data generating processes, BIC2 (assuming equal noise variances) outperforms BIC (allowing different noise variances). This holds even when the noise variances are explicitly made to be unequal, which is counterintuitive. The reverse result is obtained for the Gaussian process experiments. It’s not clear why this is happening.

- All the experiments focus on recovering the true DAG - it would be interesting to evaluate methods in terms of their performance on downstream causal inference tasks. It is easy to imagine that a slightly wrong DAG could be just as good as the right DAG for inference purposes.

- It would be interesting to see more experiments where the data-generating process and the BIC likelihood are mismatched as a way to understand robustness to model mis-specification.

- The authors observe that a standard feed-forward network fails to capture interactions between variables, which is why they used a Transformer for the encoder. Though the authors make reference to the effect of self-attention, it’s still not totally obvious why this is.

Further Reading

- Causal Discovery with Reinforcement Learning

- ML beyond Curve Fitting: An Intro to Causal Inference and do-Calculus

- Introduction to Judea Pearl’s Do-Calculus

- Review of Causal Discovery Methods Based on Graphical Models

- Deriving Policy Gradients and Implementing REINFORCE

- Understanding Actor Critic Methods and A2C