Information-Theoretic Regret Bounds for Gaussian Process Optimization in the Bandit Setting

Published:

This is a blog post credit to Jinrui Hou Zhiling Zhou Yang Liu Yibing Wei Zixin Ye

Information-Theoretic Regret Bounds for Gaussian Process Optimization in the Bandit Setting

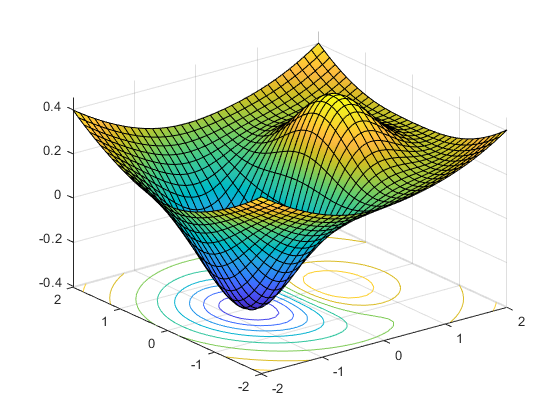

Approximating an unknown function with high-dimensional continuous input space, particularly, when noise is also presented, is never a trivial task. Such approximation can be twofold: estimation of deterministic unknown function $f$ from noisy data and optimization of our estimation over function’s domain. The former task can be achieved by well-studied kernel methods and Gaussian process (GP) model, particularly, GP regression with known covariance or Gram matrix, both of which only require the second-order statistics of training data to estimate conditional expectation and covariance of new input. The latter task, known as stochastic optimization problem, is more tricky to deal with. For instance, when data sampling needs to be minimized, i.e. collecting training data is difficult and expensive, we also need to investigate the trade-off between exploration of new sample data and exploitation of current optimal policy to maximize the cumulative reward. Therefore, the function should be explored globally with as few evaluations as possible, for example by maximizing information gain.

Numerous work has been contributed to study the convergence properties of stochastic optimization problems. For standard linear optimization in the bandit setting, whose input space is finite-dimensioned, a near-complete characterization has been proposed, the result of which is explicitly dimensionality dependent. Since the linearity assumption is too stringent, it has been relaxed to a less configurable assumption by Kleinberg et al.: only requiring $f$ to be Lipschitz-continuous with respect to the metric of function space. The bound can then be extended to the Hilbert space of GP, which can be both infinite-dimensioned and nonlinear. However, this bound degrades rapidly $(\Omega(T^{\frac{d + 1}{d + 2}}))$ with space dimension $d$ because of the Lipschitz assumption. Therefore, in the GP setting, the challenge lies in complexity characterization from the kernel function’s properties. By introducing the concept of submodularity and knowledge about kernel operator spectra, this blog will elaborate on a novel regret bound for bandit setting, developed by ML researchers in 2010, that preserves a high degree of smoothness but weak dependence on the space dimension $\mathcal{O}(\sqrt{T(\log{T})^{d+1}})$.

The blog content rigorously follows the logic of this paper. It specifically focus on GP optimization problem with multi-armed bandit setting, where $f$ is sampled from a GP distribution or has small “complexity” measured in norm of the Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS). The convergence rates are implied by a newly proposed sublinear regret bound. We will demonstrate how this bound, formulated via information gain quantity, measures the learning rate of $f$, whose submodularity also helps to prove a sharp regret bound for the kernel of RKHS, such as the Squared Exponential and Matern kernels. Finally, we give a demonstration to analyze the convergence properties of the Gaussian Process Upper Confidence Bound (GP-UCB) algorithm using this bound. The critical highlights of the blog include 1. bounding cumulative regret for GP-UCB; 2. showing sublinear regret bounds for GP optimization depending on kernel choices; 3. giving a graphical demonstration of GP-UCB realization.

Beyond the GP-UCB algorithm focused on this blog, there is a huge literature on GP optimization algorithms extending from bandits to reinforcement learning (RL) setting. For studying the trade-off between exploration and exploitation in GP optimization, many policy improvement algorithms have been proposed, such as Expected Improvement and Most Probable Improvement. Traditional Bayesian optimization and Efficient Global Optimization (EGO) can also be extended to GP setting. Yet, little is known about the theoretical performance of GP optimization, compared to its flourishing empirical findings. This makes the new sharp bound described in this blog very meaningful.

Gaussian Process and Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (RKHS)

A Gaussian process is fully specified by its mean function $m(x)$ and covariance function $k(x,x’)$. This is a natural generalization of the Gaussian distribution whose mean and covariance is a vector $\mu$ and matrix $\Sigma$, respectively. The Gaussian distribution is over vectors, whereas the Gaussian process is over functions. We write meaning: “the function f is distributed as a GP with mean function m and covariance function k”.

Modelling the unknown target function $f$ as a sample from Gaussian processs enforces the smoothness porperty and allow us to assume bounded variance by restricting $k(x, x) ≤ 1$. The two assumptions are requiered to guarantee no-regret.

In addition to the unknown target function sampled from a known GP distribution, $GP(0,k(x,x′))$ is also used as prior distribution over $f$. Furthermore, the posterior over $f$ is also a GP distribution when assuming $y_t = f(x_t)+\epsilon_t$ with $\epsilon_t \sim N(0,\sigma^2)$ i.i.d. Gaussian noise.

The RKHS is a completely sub-space of $L_2(D)$, where $D$ is our decision space. The induced RKHS norm $|f|_k=\sqrt{\langle f,f\rangle_k}$ measures the smoothness of $f$, which implies its intimate relationship to GPs and their covariance functions $k(x,x’)$.

Multi-armed Bandit and Regret

The goal of multi-armed bandit paradigm, is to maximize cumulative reward by optimally balancing exploration and exploitation. A natural performance metric in this context is cumulative regret, the loss in reward due to not knowing $f$ ’s maximum points beforehand. , where $x^* =\text{argmax}{x\in D}f(x)$ is the optimal choice , $x_t$ is our chioce in each round $t$ and $T$ is the time horizon. Ideally, the algorithm should be no-regret which means $\lim{T\to \infty}\frac{R_T}{T}=0$.

GP-UCB Algorithm

For sequential optimization, Gaussian process upper confidence bound rule (GP-UCB) combines decreasing uncertainty and maximizing the expected reward. It choose , where $\beta$ are appropriate constants. is an intuitive algorithm for GP optimization. The bound of regret is one of the key points in GP optimization. Bounding cumulative regret with information gain is a creative way to achieve this, which established a novel connection between experimental design and GP optimization.

Information Gain

Information gain is the mutual information between $f$ and observations $y_A=f_A+\epsilon_A$, where $\epsilon_A$ is noise such that $\epsilon_A\sim N(0,\sigma^2I)$ $A$ is a set of sampling points such that $A\subset D$. Therefore, the definition of information gain follows.

In our setting, information gain can be calculated with known multivariate Gaussion distribution.

And $K_A=[k(x,x^{‘})]{x,x^{‘}\in A}$ is related to covariance of $x$. Denote $F(A)=I(y_A;f)$ and $A{t-1}={x_1,x_2,…,x_{t-1}}$. Using greedy algorithm, a bound for $F(A)$ could be derived.

Bounds for Cumulative Regret

Now it is time to introduce bounds for cumulative regret. Denote $\gamma_T$ as the maximum information gain after $T$ rounds.

As we already know, $K_A$ is the covariance matrix and $f_A$ is associated with samples at each round. Thus, the bound for cumulative regret has the form $O^*(\sqrt{T\beta_T\gamma_T})$, where $\beta_T$ is the confidence parameter. After comparing with known lower bounds, this bound matches results of the $K$-armed bandit case. The results are obtained with finite $D$.

Bound I

Let $\delta\in (0,1)$ and $\beta_T=2log(\frac{|D|t^2\pi^2}{6\delta})$. Running GP-UCB with $\beta_T$ for a sample $f$ of a GP with mean function zero and covariance function $k(x,x^{‘})$, we obtain a regret bound of $O^*(\sqrt{T\gamma_T log|D|})$ with high probability. Precisely,,where $C_1=\frac{8}{log(1+\sigma^{-2})}$.

Seen from this bound, cumulative regret is bounded in terms of maximum information gain. This creates a connection between GP optimization and experimental design. Also, this bound indicates that we are able to handle infinite decision spaces.

Moreover, it is possible to derive more bounds with mild assumption on the kernel function $k$.

Bound II

Let $D\subset [0,r]^d$ be compact and convex, $d\in \mathcal {N}$, $r>0$. Suppose that the kernal $k(x,x^{‘})$ satisfies the following high probability bound on the derivatives of GP sample paths $f:$ for some constants, $a,b>0$,

where $j=1,…,d$.

Pick $\delta\in (0,1)$ and define $\beta_T=2log(\frac{|D|t^2\pi^2}{3\delta})+2dlog(t^2dbr\sqrt{log(\frac{4da}{\delta})})$.

Running the GP-UCB with $\beta_T$ for a sample of a GP with mean function zero and covariance function $k(x,x^{‘})$, we obtain a regret bound of $O^*(\sqrt{dT\gamma_T})$ with high probability. Precisely,

where $C_1=\frac{8}{log(1+\sigma^{-2})}$.

It is worth to be noticed that this bound holds for stationary kernels such as the Squared Exponential and Matern kernels, while it is violated for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck kernel. The key point here is whether the kernel function is differentiable.

Bound III

Let $\delta\in (0,1)$. Assume that the true underlying $f$ lies in the RKHS corresponding to the kernel $k(x,x^{‘})$, and that the noise $\epsilon_t$ has zero mean conditioned on the history and is bounded by $\sigma$ almost surely. In particular, assume $|f|^2_k\leq B$ and let $\beta_t=2B+300\gamma_tlog^3(\frac{t}{\delta})$ and noise model $N(0,\sigma^2)$, we obtain a regret bound of $O^*(\sqrt{T}(B\sqrt{\gamma_T}+\gamma_T))$ with high probability (over the noise). Precisely,

where $C_1=\frac{8}{log(1+\sigma^{-2})}$.

This bound is kind of similar to bound II. However, this bound holds for all functions $f$ with $|f|_k<\infty$, meaning that this bound is not dependent on sampled $f$.

Bounds for the Information Gain

Since cumulative regret is bound in terms of information gain $\gamma_T$, it is meaningful to explore further about bounds for information gain $\gamma_T$.

We have already derived a bound for $\gamma_T$ with $F(A)$. With consideration of eigenvectors of covariance matrix, a better bound could be derived.

with constraints $\sum_t m_t=T$ and $\hat{\lambda}_1\geq \hat{\lambda}_2 \geq …$

By extending this result, more interesting and useful bound could be found.

For any $T\in \mathcal {N}$ and any $T_*=1,…,T:

where $n_T=\sum^{|D|}{t=1}\hat{\lambda}_t$ and $B(T)=\sum^{|D|}_{t=T_+1}\hat{\lambda}_t$.

Two conclusions can be drawn with this bound. One is that the information gain should be small if the first $T_*$ eigenvalues carry most of the total mass $n_T$. Another one is that the speed of growth of $\gamma_T$ is opposite to the speed of spectrum of $K_D$ decays.

Bounds for Specific Kernel Functions

Let $D\subset \mathcal{R}^d$ be compact and convex, $d\in \mathcal{N}$. Assume the kernel function satisfies $k(x,x^{‘})\leq1$.

Finite Spectrum

For the d-dimensianl Bayesian linear regression case: $\gamma_T=O(dlogT)$.

Exponential Spectral Decay

For the Squared Exponential kernel: $\gamma_T=O((logT)^{d+1})$.

Power Law Spectral Decay

For Matern kernels with $\mu >1:$ $\gamma_T=O(T^{\frac{d(d+1)}{(2\mu+d(d+1))}}(logT))$.

Key Extensions

Evaluation of an unknown function has been a complex problem in machine learning for a long time. The key difficulty lies in estimating an unknown function $f$ from noisy and optimize the estimate over high-dimensional input space, of which the former has been processed by many researchers by Gaussian process and kernel methods.

The reason for which such evaluation approach is so important is that, there exists many practical problems that can be properly tackled once such evaluation is implemented. It can be employed to minimize cost for companies, maximize the profit for consumers in the long term while keeping the regret low in the short term.

For example, when choosing advertising strategy with according to user feedback to maximize profit. In this case there is no connection between how an advertisement is designed and displayed and the specific profit it brings to the company. However, it is not until the company has already advertised with enough variety can it estimate the possible profit. Therefore, Gaussian process can be employed to handle such dilemma.

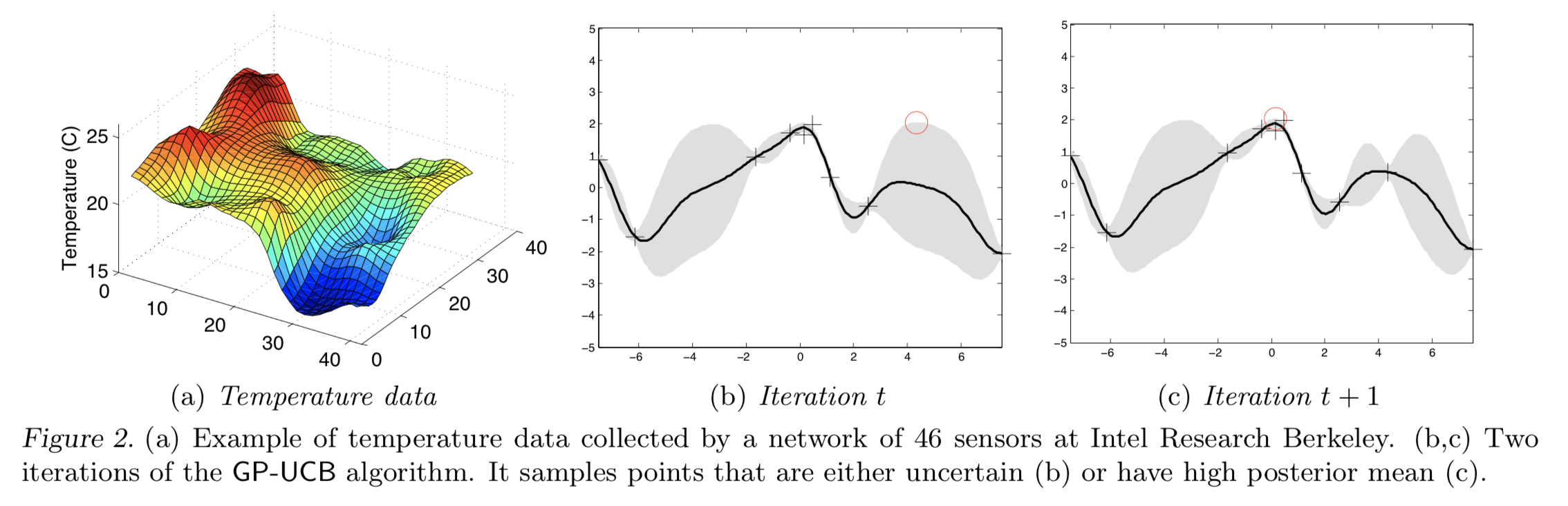

Another application is that, when someone wants to find locations of highest temperature in a building, where inactive sensors are deployed in a spatial network, by sequentially activating them. Since each activation of sensor will draw battery power, there is specific cost to activate each sensor. It is optimal to sample from as few sensors as possible while guarantees the access to the sensor with highest temperature.

To sum up, in reality there exists many practical problems which requires the evaluation of an unknown function, that is exactly what Gaussian process optimization can be employed to.

Connections to Other Topics

Related Work

This paper generalizes stochastic linear optimization in a bandit setting, where the unknown function comes from a finite-dimensional linear space.

The Gaussian processes in current paper are nonlinear random functions that can be represented in an infinite-dimensional linear space. For the standard linear setting, Dani et al. (2008) provide a near-complete characterization.

While for GP setting, the idea to bound the information gain measure using the concept of submodularity is based on Nemhauser et al., 1978. Meanwhile, Kleinberg et al. (2008) provide regret bounds under weaker and less configurable assumptions.

When it comes to GP-UCB, it aims at negotiates the exploration and exploitation tradeoff. Also, several heuristics for trading off exploration and exploitation in GP optimization have been proposed (such as Expected Improvement, Mockus et al. 1978, and Most Probable Improvement, Mockus 1989) and successfully applied in practice (c.f., Lizotte et al. 2007). Brochu et al. (2009) provide a comprehensive review of and motivation for Bayesian optimization using GPs.

Bandit and Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is an area of machine learning concerned with how software agents ought to take actions in an environment in order to maximize the notion of cumulative reward. In general, the state space of RL setting is finite dimensional. As for bandit setting, it is easier to optimize with RL algorithm. The reason is that bandit is a one state Markov Decision Process (MDP). It is convinient and reasonable to translate bandit setting into RL setting.

Gaussian Process Optimization v.s. Gaussian Process Regression

Gaussian process optimization aims at finding an optimal strategy to trade off exploration and exploitation, where exploration means choosing some suboptimal items to get more information, while exploitation means making use to current information to maximize the profit in this round.

While the goal of Gaussian process regression is to recover a nonlinear function $f$ with given data, similar to most of what regression does. It can be employed to address learning tasks in both supervised (e.g. probabilistic classification)and unsupervised (e.g. manifold learning) learning frameworks.

Learning Strategies in Gaussian Process

Thompson Sampling

Thompson sampling is an algorithm for online decision problems where actions are taken sequentially in a manner that must balance between exploiting what is known to maximize immediate performance and investing to accumulate new information that may improve future performance.

The basic idea here is playing action at each round according to the probability that maximize expected reward.

Thompson sampling and GP-UCB share a fundamental property that underlies many of their theoretical guarantees. Roughly speaking, both algorithms allocate exploratory effort to actions that might be optimal and are in this sense “optimistic.” Leveraging this property, one can translate regret bounds established for UCB algorithms to Bayesian regret bounds for Thompson sampling or unify regret analysis across both these algorithms and many classes of problems.

Sampling with Statistics

In Gaussian Process, it is required to sample from the distribution of actions and determine the next step. Thus, it is evident that some statistics may be useful to create criteria for our desicions. Normally, mean and variance are broadly used in this setting. The action that results in highest value of mean and variance will be excuted in the next round. As you can imagine, this strategy can easily arrive a local optimal point which is obviously we don’t desire to. Then comes GP-UCB which considers a upper confidence bound. With this strategy the optimization is both efficient and accurate.

More advanced numerical/empirical results

As has been mentioned before, the strategy to select points for GP-UCB consists of two terms, one of which prefers points where f is uncertain, and another term has preference for points where high rewards are expected to be achieved. GP-UCB managed to negotiate the exploration and exploitation tradeoff.

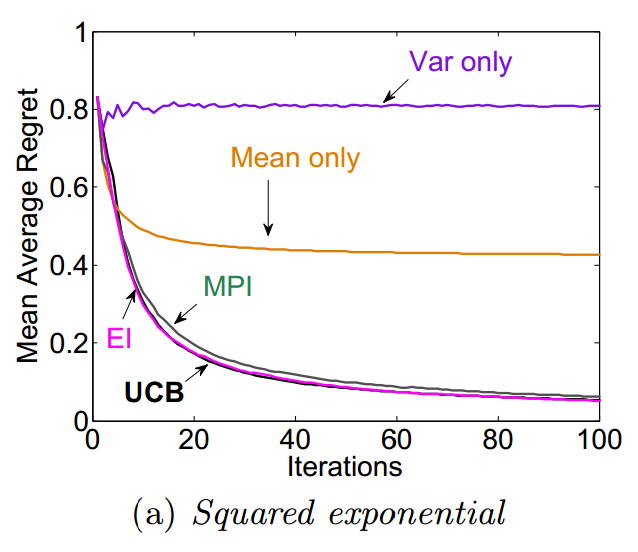

There exists many other selection strategy, including Expected Improvement(EI), Most Probable Improvement(MPI) and naïve methods which prefer points with maximal average or maximal variance only. Several experiments are designed to compare the performance between them, which will be illustrated below.

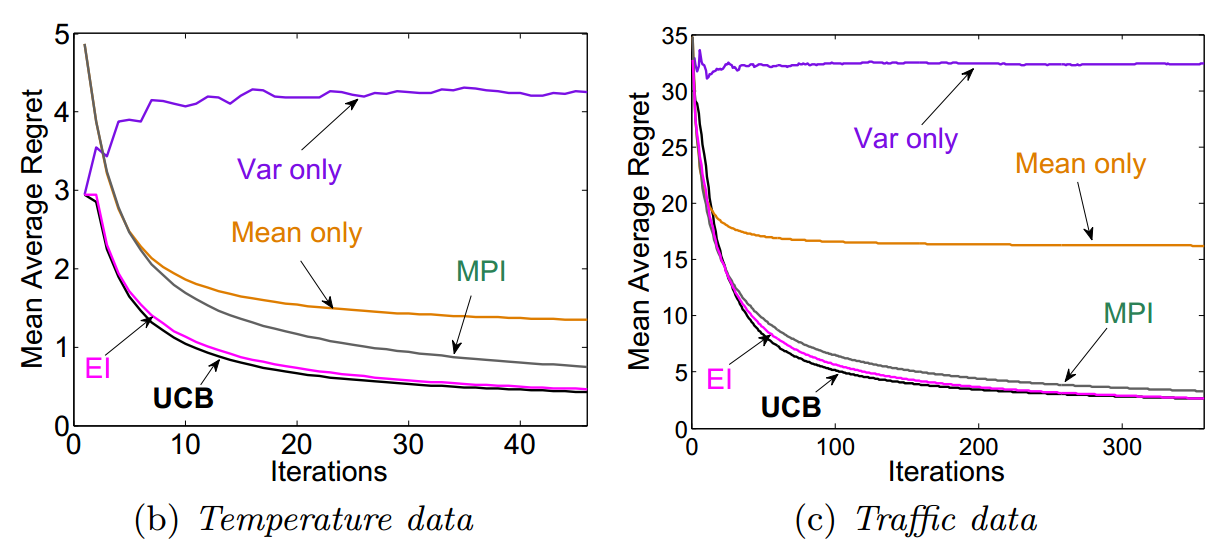

Both synthetic and real sensor network data are chosen for the comparison.

For synthetic data, it is sampled from squared exponential kernel with noise subject to normal distribution. After averaging over 30 trials to get the mean average regret, it can be clearly noticed from the plot that, GP-UCB and MPI have the lowest regret among all other strategies.

While for the two sensor network data, one of them is the temperature data collected from 46 sensors in a building over 5 days at 1 minute intervals, another one is data from traffic sensors along the highway. The performance of different models is plotted together for comparison.

For temperature data, GP-UCB and EI heuristic outperform others with show no significant difference between each other, while for traffic data, MPI and GP-UCB outperform others.

In a nutshell, GP-UCB performs at least on par with the existing approaches which are not equipped with regret bounds., which demonstrates the advantages of GP-UCB to achieve a perfect balance between exploration and exploitation. It enables the regret to be minimized while finding the best result.

Summary and Follow-up work

GP-UCB negotiates the exploration-exploitation tradeoff. Exploration means trying to discover the possible global optima outside the local optima where the exploitation is finally stuck. Exploration favors points where $f$ is uncertain. Exploitation, on the other hand, focuses on taking advantage of all the posterior data of previous time steps. In our project, we’re going to continue using the idea of the mixed strategy of both exploration and exploition. Although the study of bandit problems dates back to the 1930s, exploration–exploitation trade-offs arise in several modern applications, such as ad placement, website optimization, and packet routing. Daniel Russo et al.(2014) used a simple posterior sampling algorithm to balance between exploration and exploitation when learning to optimize actions. The algorithm used is Thompson Sampling and as probability matching, offering significant advantages over the popular upper confidence bound (UCB) approach, and can be applied to problems with finite or infinite action spaces and complicated relationships among action rewards. So exploration–exploitation trade-offs seems to be a relatively new area and worth diving deeper in.

Based on all the previous studies, the application of GP-UCB show promising results in finite arm bandit setting and linear optimization settings. However, when $D$ is infinite, it’s hard to use this mixed strategy. We are also curious about whether we can apply this mixed strategy to infinite input shape scenarios with some pre-set constriants. This may provide a better model for real-world problems.

This paper shed light on the regret bounds, or more specifically the cumulative regret bounds. In previous studies, some scholars have already connected the regret bounds to the dimensionality $d$. In another paper of the same authors, Information-Theoretic Regret Bounds for Gaussian Process Optimization in the Bandit Setting, they managed to obtain explict sublinear regret bounds for commonly used covariance functions. And in some of their important cases, their bounds have weak dependence on the dimensionality $d$. The quantity governing the regret bound problem is the maximum information gain. A lot bounds are expressed in terms of information gain. The information gain varies from problem to problem. The regret/infomation gain is determined by parameters such as kernel type and the input space. This paper provides several methods for bounding the information gain given the K-armed bandit and the $d$-dimensional linear optimization setting. Some other researchers have conducted research on regret analysis of stochastic and non-stochastic multi-armed bandit problems. In their paper, they focus on two extreme cases in which the analysis of regret is particularly simple and elegant: i.i.d. payoffs and adversarial payoffs. Besides the basic setting of finitely many actions, they also analyze some of the most important variants and extensions, such as the contextual bandit model.

Since the regret bounds depend on the information gain. This paper then shifts to the problem of bounding the information gain. The information gain is a submodular function, which requires finding the maximum value sequentially by ED rule. This paper doesn’t prove an action at time step $T$ derived by the greedy procedure makes a near-optimal information gain. It instead shows the information gain at time step $T$ is near-greedy. This greedy bound is very important. This greedy bound enables researchers to numerically compute case-by-case problems. This paper also tries to bound the information gain using different kernels like finite dimensional linear, squared exponential and Matérn kernels and compares all of them.

In the experiments, authors of the paper used temperature data, traffic sensors data. In their paper published in 2012, they again used the sensor data and found out that GP-UCB compares favorably with other heuristical GP optimization approaches. Their results provide an interesting step towards understanding exploration–exploitation tradeoffs with complex utility functions.