Learning to Optimize Discretely

Published:

This is a blog post credit to Ivan Jimenez, Bryan Yao, Jessica Choi and Serena Yan

From minimizing losses in machine learning to computing shortest paths in robotics, optimization inevitably comes forth as a fundamental framework for solving problems. In general, it tries to find an assignment of a variable $x$ that attains the minimum value of a function $f$ subject to equality and inequality constraints. We can mathematically express the previous sentence as follows:

This is a well established field in own right with powerful results. We understand the theoretical limitations of this framework. More importantly, we know the types of problems that are easily solvable and we have algorithms to compute results for real problems. Namely, this is referencing the results from convex optimziation. This field alone has provided too many useful results to enumerate. Unfortunately, for robotics and other applications, this convex optimization is not enough.

Under general convex optimization we would assume functions $f$ , $g$ and $h$ are convex and all decision variables are real. In the case of Mixed-Inter Programming (MIP) we want to slightly change these conditions as follows:

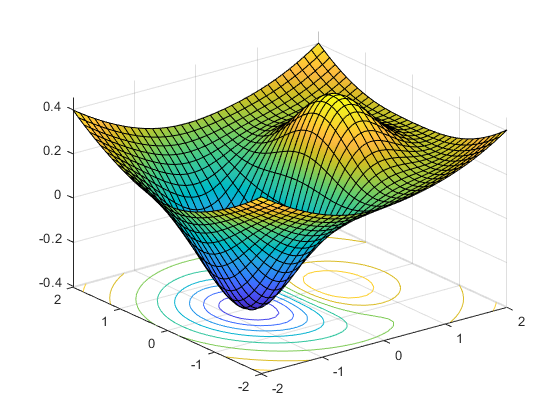

The integral integral variable $x_2$ completely changes the expressiveness of the original problem. Instead of solving a single convex optimization program we can think of this as finding the optimal assignment of $x_1$ across all possible combinations of admissible $x_2$ values. This framework has proven particularly useful to tackle certian types of non-convex optimization problems. It’s utility becomes apparent when plotting mixed-integer approximation of a non-convex problem:

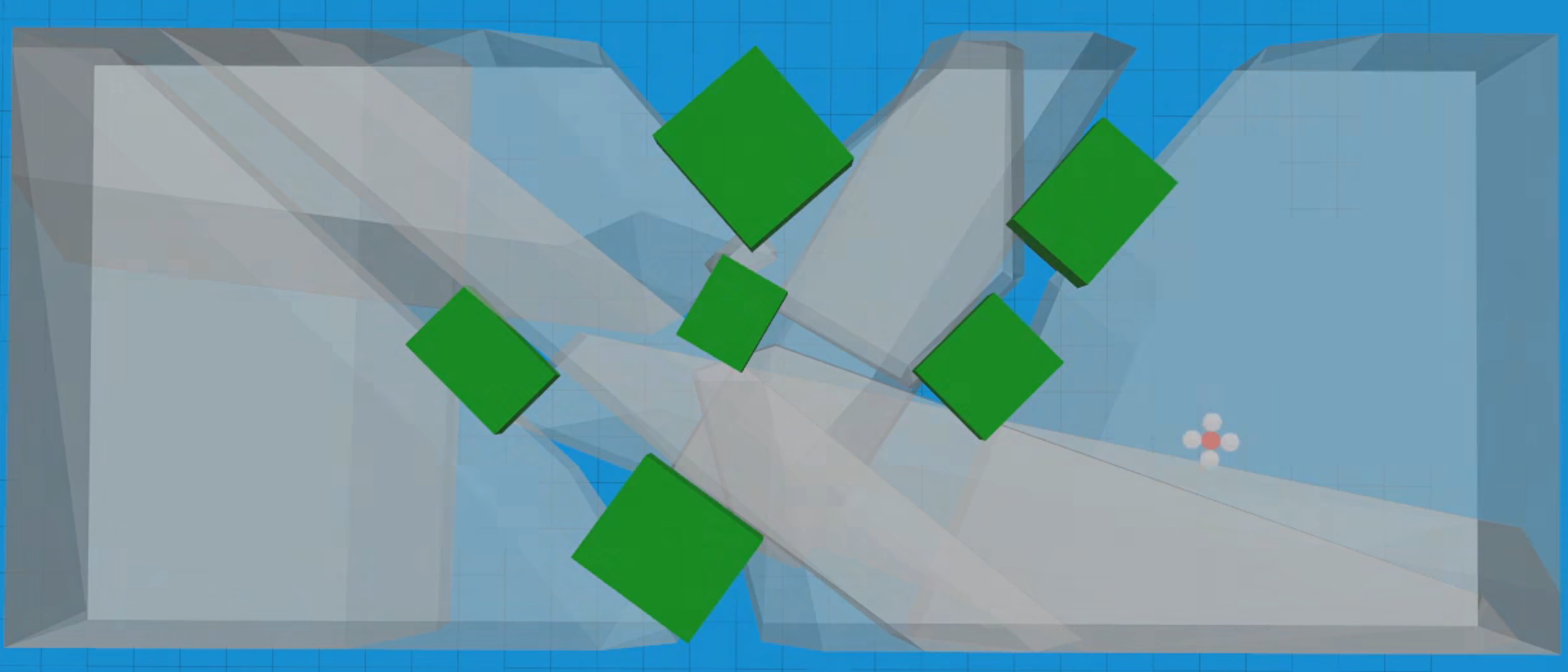

This is a UAV using MIP to plan path from one side of the room to the other while avoiding obstacles. Although the obstacles could be represented in a non-convex optimization program, an MIP can use a set of Convex optimization programs with a set of convex constraints to approximate the original problem. Similar techniques have been used in humanoid robots for Footstep Planning and Walking.Overall the key insight of these contributions is that by understanding the structure of the problem an intractable non-convex optimization program can be approximated well with an MIP. These approaches rely solely on the structure of the problem to arrive to a policy. Thus, no data set or training is required for those highly general algorithms to work. Unfortunately, directly programming robots this way to achieve the range and sophistication of policies we want is prohibitively expensive.

On the other hand, machine learning and in particular Reinforcement learning has proven to be extremely successful at robotic similarly complex tasks. Consider for example having robots mimic human movement orgrasp objects with visual feedback. Even more generally there have been outstanding results in games with discrete action spaces like Go and Star Craft.Sadly, these methods based solely on reinforcement learning can pose serious risks to robots during training in dynamic environments and require enormous amounts of data.

Could we perhaps combine machine learning with the discrete structure of MIPs to generate more sophisticated policies than humans could program while keeping the data requirements reasonable? We present three approaches to this particular problem.

Learning to Search in Branch and Bound Algorithms

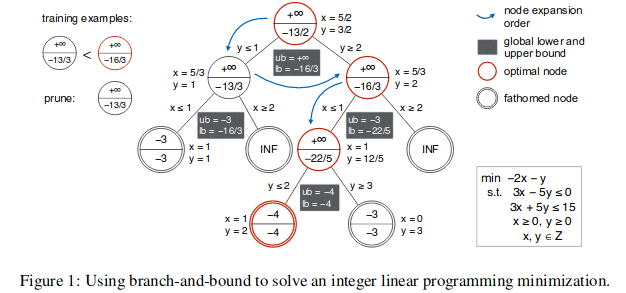

Branch \& bound (B\&B) is an optimization algorithm often used to solve mixed integer linear programming (MILP) problems. At a high level, it does so by solving the LP relaxation of a given problem (removing the assumption that the solution must be within the integer domain) at the root node, and branching from that (if the solution has non-integer values), creating new subproblems (child nodes) by adding new bounds to the problem. These subproblems are then solved, and if the solution still contains non-integer values, is branched from with new bounds and so forth, until the optimal integer-domain solution is found. The following tree graphic visualizes this decision process:

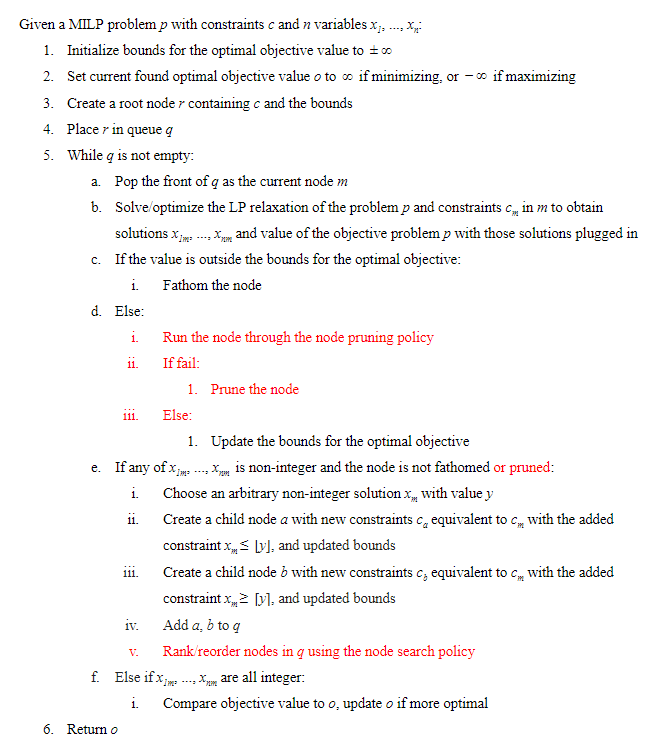

To find the optimal solution this way with the generic B\&B algorithm can be computationally expensive. As the number of variables increases, the number of nodes that have to be processed could potentially increase exponentially. The paper attempts to more efficiently solve MILP problems with B\&B by identifying nodes with a higher likelihood of leading to the optimal solution and evaluating them earlier, and pruning nodes that seem less promising. Imitation learning is used to train policies to implement this automatically. Oracles that know the optimal branching path are used to help the model learn behaviors for node search/selection and pruning policies. The pseudocode below details the B\&B algorithm, with red steps indicating modifications from the paper’s model.

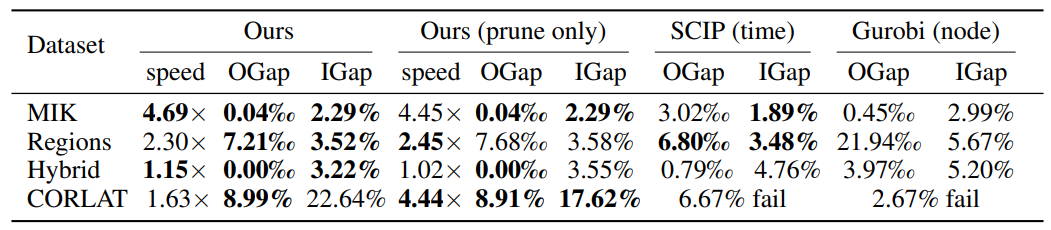

This algorithm improves on running time by trading optimality of the solution with the assumption that the heuristic path generates a good solution. This guarantees an upper bound on the expected number of branches. The following table shows that this bound actually hols in practice with four different problems:

The method proposed by the paper was tested against methods of solving MILP problems from existing libraries (SCIP, Gurobi). Both a version of the proposed method with search and pruning policies as well as a version with only the pruning policies was tested. These were evaluated on speedup (“speed”), the runtime comparison to the time it takes for SCIP to find the optimal solution with no time limits, optimality gap (“OGap”), the percent difference between the value of the final objective found by the method compared to that found by SCIP, and integrality gap (“IGap”), the percent difference between the upper and lower bounds for the objective at the solution node. The latter two methods tested were SCIP and Gurobi with a time and node limit, respectively, set to make them take as much runtime as the paper’s proposed model (first column), and thus are only evaluated on OGap and IGap. On simpler MILP problems (MIK), the paper’s proposed method recorded a speedup factor of 4.7 with a loss in solution quality of less than 1\% - on harder MILP problems (CORLAT), the loss was larger, but within 10\%. On CORLAT, both bounded SCIP and Gurobi were not capable of finding a feasible solution within the limit. The bolded numbers indicate the best performers for that measure, within a range determined by a t-test with rejection level 0.05. From this we note that the paper’s proposed methods perform the best or close to the best for all the tested problems.

Learning Combinatorial Optimization Algorithms over Graphs

Often, graphs are useful as an equivalent representation of a discrete optimization problem. The three main ways to tackle these NP-hard graph optimization problems are through using exact algorithms (such as branch-and-bound), approximation algorithms, and heuristic functions. None of these exploit the fact that many real-world problems maintain the same overall structure and mainly differ in data. Thus it is possible to learn how to solve a class of graph optimization problems in such a way that the solution can be applied to similar problems that haven’t been seen before.

This paper uses a greedy meta-algorithm design and represents it in a graph embedding network, which creates node and edge embeddings that are condensed properties of each part in relation to its neighbors. Then, this algorithm is trained incrementally using fitted Q-learning to optimize the objective function of a problem instance, such that each new node can provide benefit to the final solution. By learning the evaluation function Q over a set of problem instances, instead of defining Q as is usually done in typical greedy algorithm design, the authors save a substantial amount of time understanding the problem and testing theories. For the graph embedding, an architecture called structure2vec is used to convert each node into a n-dimensional feature vector, which is updated at each iteration based on the graph topology. After $T$ iterations, the learned embeddings for each node and pooled embeddings from the entire graph can be used in Q as surrogates for selecting the best node to add next.

Reinforcement learning can be used to learn Q when there are no training labels, such as with the maximum cut (MAXCUT), minimum vertex cover (MVC), and traveling salesman problems (TSP). The state $S$ is defined to be the sequence of actions (the addition of nodes) on a graph $G$, and we know that the embedding representation can be applied to many problem instances since the nodes are represented as $n$-dimensional vectors. The transition is the most recently added node. The actions are the nodes in $G$ that haven’t been added to $S$ yet, so the possible nodes that we can still add. The reward is defined as the change in the cost function from adding a node, and this aligns perfectly with the objective function value of the terminal state. We will use $Q$ as the policy, which will greedily choose the node at each iteration that maximizes the reward.

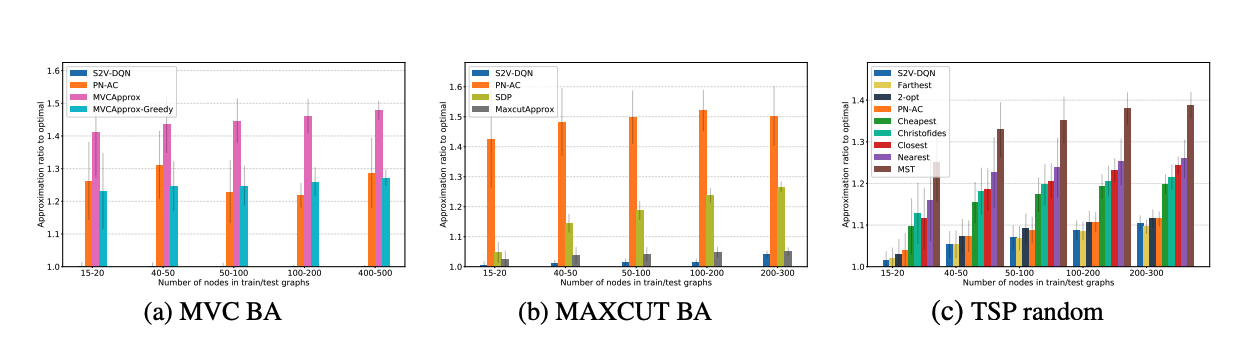

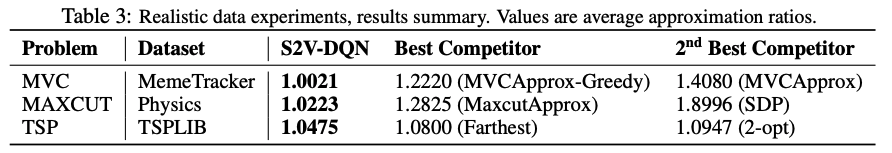

For testing, many graph instances were generated for each of the problems in (MAXCUT, MVC, TSP) and the proposed algorithm (S2V-DQN) was tested against powerful approximation or heuristic algorithms from research, such as Pointer Networks with Actor-Critic (PN-AC), which is an algorithm for the TSP based on RNNs. Approximation ratio of a solution, defined as the objective value of the solution S compared to the best known solution value for the problem instance $G$, was averaged over all problem instances in the test set and evaluated for each algorithm. The following shows the approximation ratio for $1000$ test graphs:

We observe that S2V-DQN significantly outperforms the other algorithms in nearly every combination of problem space x number of nodes in the graphs. In addition to the generated data, these algorithms were tested on benchmark or real-world instances for each problem. Again, we observe that S2V-DQN outperforms the state of the art.

Therefore, this framework for solving a class of graph optimization problems is proven to be more effective than existing solutions to each individual problem. Using reinforcement learning to greedily optimize the evaluation function, which is parameterized by the graph embedding network, shows excellent performance when compared to manually-designed greedy algorithms even when generalized across many types and sizes of graphs.

Large Neighborhood Search (LNS)

LNS vs. domain specific heuristics

Historically, Integer Programming (IP) optimization problems are solved using domain specific heuristics such as Branch-and-Bound and Select Node. However, these heuristics are highly dependent on domain specific knowledge. tackles this problem by providing a data-driven and general learning heuristic to solve IP optimization problems. For many problems, LNS is as competitive or even outperforms the best manually designed heuristics. Thus, the LNS approach is a promising direction for the automated design of solvers that avoids the need to carefully integrate domain knowledge.

General Framework

First, LNS requires an initial solution that could be far from optimal. Then, LNS obtains a decomposition of set of variables, $X = X_1\bigcup…\bigcup X_k$, either through a random number generator or learning methods. Then, for each iteration, LNS fixes all variables except the ones in $X_i$ and solve optimally for $X_i$. Each subproblem is a smaller IP problem and can be solved using off-the-shelf solver such as Gurobi. We repeat the above with different decompositions and return the best decomposition found.

The paper explored learning the decomposition using imitation learning. In BC, demonstration (generated by choosing the best decompositions from the randomly generated decompositions) serves as learning signals. The main idea is to turn each demonstration trajectory into a collection of state-action pairs, then treat policy learning as a supervised learning problem. In our case, the action is a decomposition and state is the assignment for variables in $X$ (solution to the optimization). However, BC is prone to cascading errors. To overcome this, the paper proposed an adapted forward training algorithm where demonstrations are not collected beforehand, but rather collected dependent on the predicted decompositions of previous policies.

Performance of LNS

Four IP problems are used to test the performance of LNS: minimum vertex cover, maximum cut, combinatorial auctions, and risk-aware path planning. For all four problems, all LNS variants significantly outperform Gurobi (up to 50 percent improvement in objectives), given the same amount or less wall-clock time. Notable, this phenomenon holds true even for Random-LNS. For the risk-aware path planning problem which applies the most to our project, the imitation learning based variants, FT-LNS and BC-LNS, outperform Random-LNS and RL-LNS by a small margin. Especially in the wall-clock case, the two imitation learning LNS have significantly larger decrease in change in objective value in the first few seconds (2 or 3 seconds) than random-LNS, RL-LNS, and Gurobi. This means that FT-LNS and BC-LNS provide better performance for problems that must be solved in a very short period of time, which is very important in real world problems such as motion planning for robots and games.

applying LNS to our project

For our specific project about motion planning in robotics and games, we want to focus on solving the Risk-Aware Path Planning problem using LNS. The paper only explores the most basic type of risk-aware path planning problem in 2d coordinates. For our project, we aim to modify the problem to 3d space and add in more features (such as physics and limitations) and analyze the performance of LNS on the modified problem.

final thoughts

Because of the generality of MIPs, there are a wide variety of approaches to improve their performance with learning. Above, we barely touched on some of them. We even skipped over the entire field of differentiable optimization presented in seminal works like OptNet and SATNet.

More importantly, we see a lack of applications of these papers to the robotics setting which should be particularly well suited. Notice that simple tasks like motion planning or model predictive control, roboticists are interested in solving a sequence of similar problems. This gives us hope that experience distilled from data could potentially improve performance significantly. For high-dimensional robotics system like those modeled in foot step planning, an algorithmic improvement could change the approach from offline trajectory generation to online planning. Throughout the rest of the course this is the vein of problems we wish to explore.